Using COVID-19 Case Data Alone Will Fool You

26 April 2020

Originally posted on medium.com

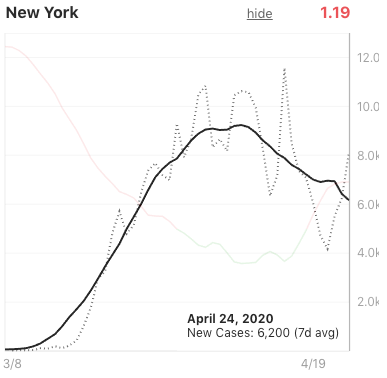

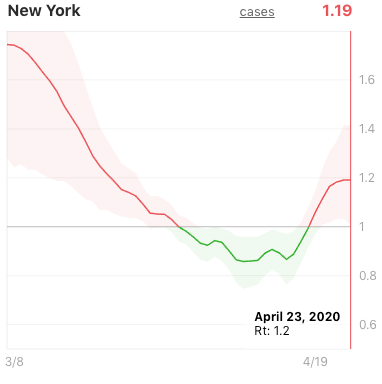

Recently, several prominent analyses have relied on reported cases of COVID-19 alone to draw important conclusions. One major example is that of Kevin Systrom’s (of Instagram fame) valiant effort to estimate the most important metric of this ongoing epidemic, the reproduction factor. Take a look at his estimates for New York State:

Understanding what is happening to the reproduction factor is so important because if the value is above 1 then the disease is spreading exponentially and if it is below 1 then the disease will eventually die out. In Kevin’s model, the reproduction factor falls below 1 as of March 31, about a week after the state went on lockdown. That seems plausible. But, then on April 19 the value jumps up above 1 and stays in that range for the next week. Why would that happen? New York is still on lockdown and hospitalization data shows that hospitalizations in the state continue to fall.

[Side note: Kevin’s estimate of a reproduction factor below 2 throughout March in NY is much lower than the mainstream view and contradicted by other data. But I will explain that in another post.]

So, what gives? Why is Kevin’s model suggesting that the disease is growing again in NY? Is it actually true? Should we be worried?

Kevin’s model is quite complex and impressive, using sophisticated statistical techniques like Gaussian distributions and maximum likelihood estimators. At the model’s core however is the idea that you can learn about the disease’s spread rate just from the reported cases.

The dashed line in this chart is the number of cases reported daily and the solid line is a smoothed version of the same data. Kevin’s model for the reproduction factor is picking up on that recent uptick in the dashed line, but that doesn’t mean we should be freaking out.

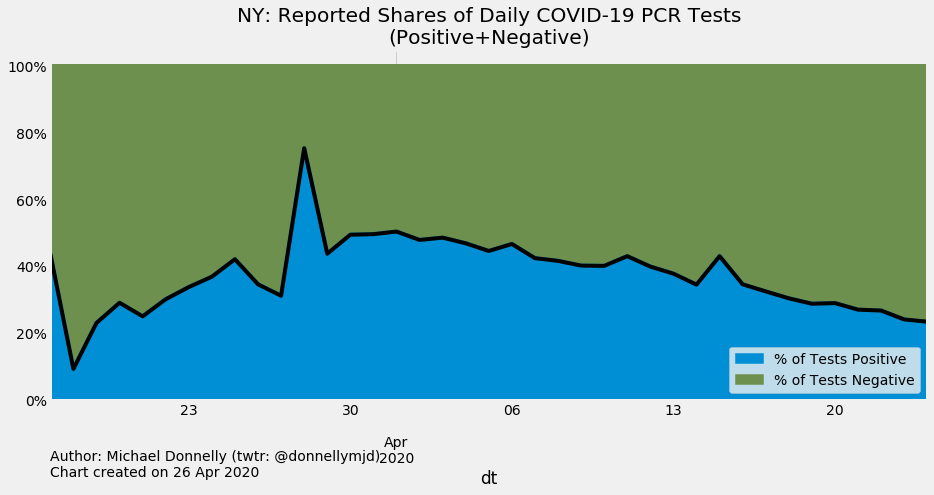

Take a look at the trends in the total number of daily tests given in NY. At the same time that Kevin’s model is picking up on an increase in positive test results, NY is increasing the number of people who get tested!

What actually seems to be going on is a slight but continued downward trend consistent with our expectations of a reproduction factor below one. While it is possible that the disease has started to spread exponentially at the same time that NY has increased testing, it would be quite the coincidence. We know that tests aren’t capturing everyone who has been infected and finding them is a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack. The recent uptick in the positive tests is likely a reflection of the fact that we have gone through more haystacks recently.

It is entirely understandable why Kevin relied on positive tests for his model. There is extremely limited data sources available to researchers trying to help inform the public and policymakers right now. But, we have to be careful that models built on faulty data do not lead to bad decision-making. In this case, had New York’s policymakers taken Kevin’s estimates of an increase in the reproduction value at face value, they could have made costly decisions that may have unnecessarily delayed some mild relaxation of the mitigation strategy currently in place.

The bottom line is that positive test data alone does not give us enough information to draw a strong conclusion about what is happening with the spread of COVID-19, especially when there are big changes to who gets tested and how many tests are given. Truly randomized population testing is the most statistically sound method for tracking the spread of COVID-19 and it is not happening broadly in the US yet. The sooner that happens, the better.

Please stay tuned for a future note which will discuss another methodology for identifying the reproduction rate that avoids some of the pitfalls mentioned above.

Note: All of the testing data in this note generally refers to RT-PCR tests that look for evidence of the virus. Antibody testing (also known as serological testing) has gotten a lot of attention in the news recently. The data in this note does not reflect antibody tests.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/0*ZL6JYvj81p-G8H13)